Most of us understand that a life-threatening experience can shake your sense of who you are and what it means to be in the world. Physical injury aside, some people are never quite the same again. Some, however, seem to find healing from trauma a manageable process. Some go on to become fantastic healers or inspirational figures, while others will struggle for a while and then get on with the lives they’d always intended to lead.

Yet any life transition, particularly if sudden and unexpected, has the potential to have traumatic impact. Events beyond your control like relationship break-up, redundancy, miscarriage, bereavement or stroke can pose an overwhelming threat to your sense of self. Even changes planned or hoped for, like relocating or winning the lottery, can catapult you into an unanticipated new reality requiring trauma management.

Psychological trauma arises from an serious challenge to a your reality. A car accident, for example, is a betrayal of the assumption that your car is a safe, comfortable personal space. It can shake all the other assumptions forming the foundations of your existence – so can discovering your trusted partner has been having an affair, or the bank repossessing your lifelong home. Your life doesn’t have to be in danger for your psyche to perceive the threat of annihilation.

Whether or not you’re psychologically damaged by any shocking experience, life threatening or otherwise, seems to depend on how it’s processed. Your ability to integrate an experience might be affected by patterns set by earlier traumas, or perhaps your life experience so far makes you inexperienced in change management.

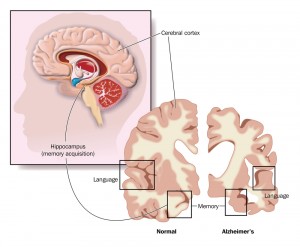

Our brains manage memories in two distinct ways. The Hippocampus stores autobiographical data for retrieval at will. Facts we know about what happened to us, when, where and who with, are retained as if in a filing system and we choose when to reminisce or to consider and learn from our experiences. We can also reframe these conscious memories later to incorporate new information or learning.

Another component of memory is stored in the Amygdala, the area which neurologists suspect is responsible for unconscious ‘fight or flight’ impulses. Ideally, these unconscious ‘feeling’ memories are released only in context via the associated conscious recollections. The two parts of the brain can then work together to resolve any emotional or psychological distress associated with the memory – for example, if something upsetting happened at work, you can talk to a friend, and explain what you’re feeling and why.

A crisis can temporarily shut down the Hippocampus, letting the Amygdala take over. This is appropriate during a life-or-death situation, when awareness of danger is more important than understanding the situation. Afterwards it gives you the chance to escape from any continued danger and find a more secure space in which to adjust your world view. The feelings may then begin surface without a conscious component (for example as dreams, or flashbacks) until the Hippocampus steps in to allow you to understand there’s no longer an imminent threat.

Things can go awry if the memory is too painful to consciously contemplate. You can get stuck in the unconscious state, constantly re-experiencing debilitating emotions, yet unable to understand or deal with them. This can be as true of a devastating conversation as of a natural disaster.

While your mind tries to protect you by blocking conscious recollection, the associated emotions wreak havoc in your life. This is what’s known as PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder. It doesn’t just happen to war veterans!

If you recognise any of this from your own life, help is at hand. My company’s cathartic approach works to shift the unhelpful block to understanding by first creating a healing ‘cocoon’ of non-judgmental emotional support in which your distress can be safely acknowledged. The experience can then be processed, ‘filing’ the feelings with their conscious memories where they can contribute to your growth as a person.

During a period of reflective ‘metamorphosis’, you make the transition to a new and constructive outlook orientated toward the future rather than reacting to the past after which the new, wiser you emerges butterfly-like, ready to embrace the challenges and opportunities generated by change.

For more information about how transitions impact the brain and how individuals’ past traumas can impact your change programmes, get in touch with me.

Till next time